The New Documents was an influential documentary photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York curated in 1967 by John Szarkowski. It featured work by three (then) young and relatively unknown photographers - Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand - and had a lasting influence on modern photography. As curator John Szarkowski explained in his introduction to the exhibition, the three represented a new generation of photographer with markedly different aims than those of their predecessors of the 1930s and 1940s: they had “redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it.” The exhibition established all three photographers as important voices in American art and their achievements continue to encourage more nuanced understandings of the medium. The exhbition is said to have “represented a shift in emphasis” and “identified a new direction in photography: pictures that seemed to have a casual, snapshot-like look and subject matter so apparently ordinary that it was hard to categorize”.

The exhibition itself was modest by today’s standards: small, framed black-and-white pictures arranged in two galleries on the museum’s ground floor. The works on display possessed a casual, offhand quality and the subject matter was so apparently random and ordinary that the public had a difficult time comprehending what the pictures were trying to say. Critics, too, were skeptical. “The observations of the photographers are noted as oddities in personality, situation, incident, movement, and the vagaries of chance,” Jacob Deschin wrote in a Times review. He could not identify the subject of documentation in any of the works on display, or any discernable point to the show.

In the past, photographic practice had typically been defined by its ability to provide proof, or documentation, of a specific subject: Walker Evans’s photographs of Southern migrant workers, for example, conveyed an almost forensic objectivity and clear-eyed purpose; whether August Sander’s portraits of Germans before the rise of Hitler, Lewis Hine’s photos of child laborers, Aaron Siskind’s “Harlem Document,” or Helen Levitt’s pictures of children on the streets of New York, photographers were known primarily for their visual description of a particular subject, often with the underlying purpose of exposing the world’s ills and generating interest in fixing them.

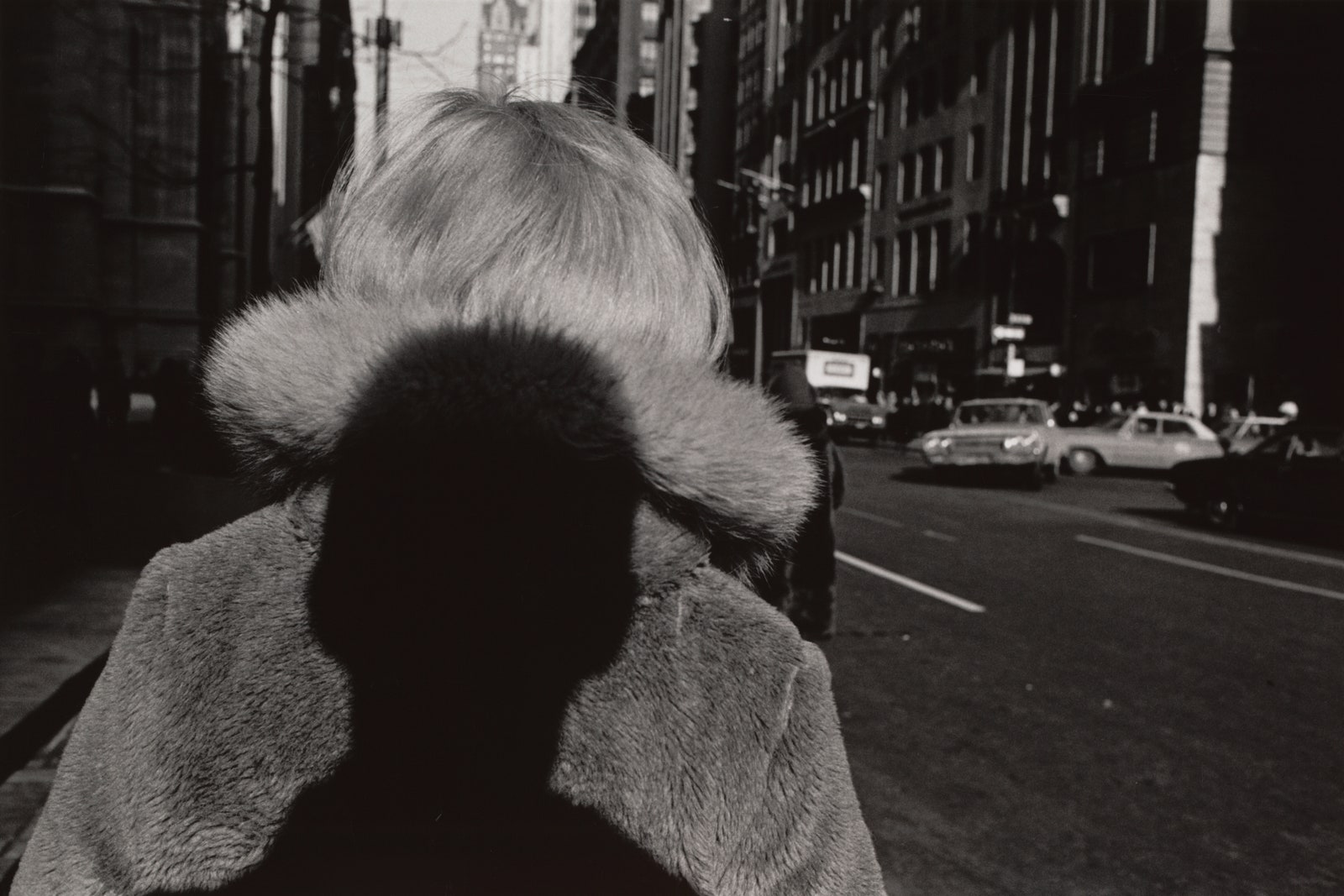

In a statement posted on the gallery wall, Szarkowski described “New Documents” as a showcase for a new kind of photograph, from a generation of artists who had embraced an almost existential attitude toward the medium, adopting “the documentary approach toward more personal ends.” This new photographic style, pioneered a decade before, by Robert Frank, in “The Americans,” combined the informality of the family snapshot with the authenticity of documentary photography and the immediacy of a news picture. For these new photographers, the camera was not only a tool for recording and describing the world but for recognizing and examining their personal interactions with it. As Winogrand famously put it, “I photograph to see what things look like photographed.”

It’s hard to overestimate the influence that these modest, slice-of-life scenes would have on subsequent generations of photographers, or Szarkowski’s curatorial vision in conferring importance on the work of these artists. The year that “New Documents” was mounted, Szarkowski was the presiding authority in the field of photography, and his platform at the museum was nothing less than the seat of judgment. Yet he remained self-effacing about his role in shaping the trajectory of the medium: “I think anybody who had been moderately competent, reasonably alert to the vitality of what was actually going on in the medium would have done the same thing I did,” he said.

Diane Arbus, known for her intimate and often unsettling portraits of individuals on the fringes of society, played a crucial role in reimagining documentary photography. Arbus sought out subjects that were often marginalized or deemed outcasts, challenging societal norms and perceptions. Through her lens, she revealed the complexity and humanity of her subjects, evoking both empathy and discomfort in viewers. Arbus’s images confronted viewers with the “otherness” that exists within society, prompting reflection and questioning of preconceived notions.

Lee Friedlander embraced a more experimental and playful approach to documentary photography. His images often featured reflections, shadows, and unexpected juxtapositions. Friedlander’s photographs captured the chaotic and fragmented nature of urban life, revealing the layers of visual information that surround us. His work challenged traditional compositional rules and expanded the possibilities of visual storytelling.

Garry Winogrand, known for his prolific output and unflinching depiction of American life, also contributed to the reimagining of documentary photography. Winogrand’s images were characterized by their raw energy and spontaneity. He immersed himself in the streets, capturing the essence of everyday life and its eccentricities. Winogrand’s photographs were often marked by a sense of ambiguity, leaving room for interpretation and inviting viewers to engage actively with the images.

The New Documents photographers shared a common interest in the human condition and a desire to explore the complexities of society. They embraced a subjective and personal approach, challenging the notion of objectivity in documentary photography. Their work offered a fresh perspective, depicting the world through their own distinctive lenses. In doing so, they expanded the possibilities of what documentary photography could be.

The impact of The New Documents movement was significant, both within the world of photography and beyond. The movement challenged established conventions and opened up new avenues for creative expression. By focusing on the everyday and the marginalized, these photographers brought attention to overlooked narratives and alternative perspectives. Their work invited viewers to question societal norms and to see the world in a different light, shaping the trajectory of documentary photography for future generations. Its emphasis on personal experience and the exploration of subjective truths paved the way for photographers to infuse their own perspectives and voices into their work. The movement’s legacy can be seen in contemporary documentary photography, where photographers continue to challenge conventions and explore new ways of storytelling.