The emergence of Modernism in photography marked a significant turning point in the history of the medium. The early 20th century witnessed a departure from traditional photographic conventions, as photographers sought to break free from the limitations of objective representation and explore new ways of seeing and interpreting the world. The medium splintering into different movements reflected the political and cultural changes in the arts and society in general. If photography’s trajectory in the nineteenth century was always one step removed from the major art movements of the era, it collided head on with them from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Cubism’s engagement with mechanical form hinted at the role photography would soon play within the avant-garde, and both the Dada and Surrealist movements saw the potential of this youthful medium. In the Weimar Republic, the Staatliches Bauhaous photography at the behest of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who dominated the cultural landscape with his photograms and angular shots of landscapes. In the Soviet Union, photoography was in the vanguard of a movement that pushed for radical societal change. Alexander Rodchenko gave up painting to develop a photographic style that, like Moholy-Nagy’s, embraced oblique perspectives, often from above. But his work, along with that of El Lissitzky, Gustav Klutis and Max Penson, which aimed to capture the momentum of mondern life, was compromised by Stalin’s brutal regime.

Modernism in photography challenged the established practices of the time, which primarily focused on capturing objective reality. Photographers sought to move beyond mere documentation and embrace subjective interpretation, experimentation, and innovation. This departure from tradition allowed for a fresh approach to photography as a means of artistic expression.

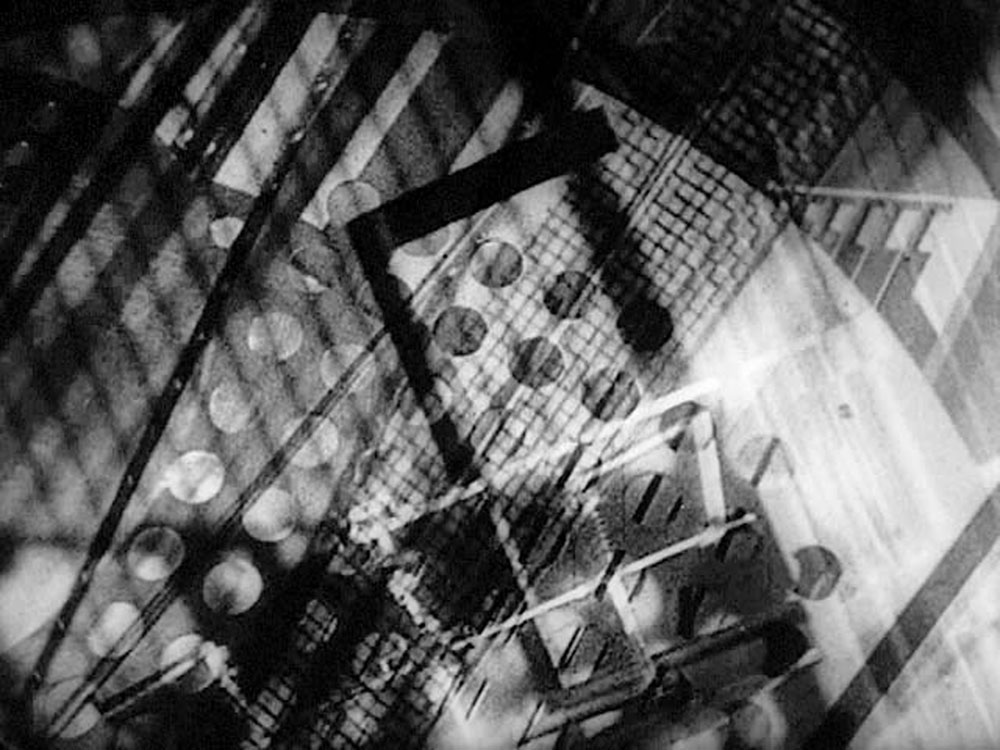

Modernist photographers embraced abstraction by deconstructing subjects into their essential forms and focusing on geometric shapes, lines, and textures. They fragmented reality, capturing unconventional angles and viewpoints that revealed the hidden beauty and complexity of the world.

Experimentation with technique was a hallmark of Modernist photography. Photographers pushed the boundaries of photographic technique, exploring new methods of exposure, printing, and manipulation. They employed multiple exposures, photomontage, and other experimental techniques to create unique and often surreal images.

Dynamic composition played a crucial role in Modernist photography. Photographers rejected the traditional rules of composition and sought to create dynamic and visually compelling images. They played with asymmetry, diagonal lines, and unconventional cropping to challenge the viewer’s perception and create a sense of movement and energy.

Several influential photographers emerged during the era of Modernism. Man Ray, a prominent figure in the Surrealist movement, experimented with techniques such as solarization and photograms, creating dreamlike and abstract images that challenged conventional representation. Edward Weston, known for his precise and detailed close-up studies of natural forms, exemplified the Modernist approach of exploring the inherent beauty and abstract qualities of everyday objects. László Moholy-Nagy, a key proponent of the Bauhaus movement, pushed the boundaries of photography by incorporating industrial and architectural subjects. He embraced avant-garde techniques such as photomontage and photograms to explore the potential of photography as a medium for experimentation.

Modernism in photography had a profound impact on the medium, influencing subsequent artistic movements and shaping the development of photography as an art form. It challenged traditional notions of representation, expanded the possibilities of visual expression, and opened doors for experimentation and innovation. The exploration of abstraction, unconventional techniques, and dynamic composition paved the way for future movements such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Conceptual Photography.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy was an innovator not only in photography, but also in typography, sculpture, painting, printmaking and industrial design and arguably the most influential photographer within the German avant-garde, although Hungarian by birth. He believed that photography offered a universal visual language ideally suited to the progressive needs of modern society. His ‘New Vision’ could establish a new relationship with the visible world and overcome the limitations of human sight by challenging conventional ideas of vision, space and light. The New Vision also embraced unconventional forms and techniques, such as photograms and photomontages that combined photographs with modern typography.

Held in Stuttgart in 1929, the ‘Film und Foto’ (Film and Photo) exhibition showed the work of avant-garde artists from Western Europe, Russia and the United Sates and brought together the avant-garde photographic and cinematic trends of the 1920s. A groundbreaking book, ‘Es Kommt der Neue Fotograf! (Here Comes the New Photographer!), which accompanied the show, illustrated definitive strategies such as angling the composition, shooting up or down and creating montages. The ‘Film und Foto’ exhibition poster designed by Jan Tschichold and featuring a photograph by Willi Ruge emphasized the exhibitors desire to educate viewers in the principles of the New Vision. It was a radical departure from the photographic norms of the 19th century. The Leica camera, a compact marvel, made its debut on the market, affording photographers fresh perspectives on the world. Gone were the days of stagnant, horizontal compositions. Photographers like Alexander Rodchenko in the Soviet Union, François Kollar, and Pierre Boucher in France, seized the moment. They delved into uncharted waters, adopting daring angles, dynamic diagonals, and breathtaking close-ups. These pioneers fragmented reality and birthed a new visual language.

Equally as influential as Moholy-Nagy was Albert Renger-Patzsch, who championed the aesthetic ideology known as New Objectivity. The movement, initially developed by German painters between the wars as a response to Expressionism, never had a formal manifesto – taking its name from a 1923 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mannheim organized by director Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub. Photography was well suited to the aims of New Objectivity, which rejected the self-involvement and romantic longings of the expressionism. The images were not subjected to the photographer’s subjective vision or eye-catching compositional strategies. The role of the photographer was to document reality in an unsentimental and naturalistic manner – enhancing the appreciation of an object by reproducing it in fine, realistic detail. This was often accomplished by placing the subject in the centre of the perfectly proportioned frame, giving the viewer no option but to ponder the subject itself.

One of its most important practitioners was August Sander, who recorded his many subjects in somber, inexpressive poses, which he then arranged according to profession, such as Cleaning Woman, Pastry Chef, and Bricklayer. Besides traditional occupations, Sander also chronicled the new professions of modern society, as in his Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne. With her bobbed hair, loose clothing, and confident gaze, she depicts so-called “New Woman” whose entrance into the workforce emancipated her from many of the restrictions faced by women before the war. The view should not be subjected to the photographer’s subjective vision or eye-catching compositional strategies and the role of the photographer was to enhance the appreciation of an object by reproducing it in fine, realistic detail. This was often accomplished by placing the subject in the centre of the perfectly proportioned frame, giving the viewer no option but to ponder the subject itself.

The advent of Modernism in photography marked a significant shift in the perception and practice of the medium. By challenging traditional aesthetic and technical conventions, Modernist photographers embraced subjective interpretation, experimentation, and innovation. Their exploration of abstraction, fragmented reality, and dynamic composition expanded the artistic possibilities of photography and influenced subsequent artistic movements. The legacy of Modernism in photography continues to resonate today, reminding us of the power of the medium to capture and interpret the world in new and transformative ways.