By the mid-nineteenth century early photographic practices were already starting to mature and journalism was quick to see the benefit. Coverage of the Crimean War (1853-56) was the first significant role played by photography in mass media, when the British Government hired photographer Roger Fenton to document the war for The Illustrated London News. The images were intended to balance critical reporting from other outlets and ease the general unpopularity of the war among the British people. With this objective in mind, and the bulky equipment required of early photography, Fenton didn’t photograph the war directly at the frontline but focused on everything surrounding the war, including landscapes, staged portraits and logistical operations. The resulting images therefore offered a fairly tame and romantised view the conflict, distracting the audience from any perceived mismanagement.

The following decade, photographic coverage of the American Civil War (1861-65) revealed the true potential of the medium. Photography was becoming more accessible every year and thanks to the work of photojournalists, the general population witnessed the reality of warfare for the first time. Before, depictions of war were limited to illustrations or paintings, providing a view of war highly influenced by a single artist’s perspective. Now, through photography, the situations displayed might still have been affected by the photographer’s interests, but the combination of all the archives from both sides of the conflict gave a realistic insight into the reality of war. Mathew Brady rose to prominence during the period as he was not only a photographer himself, but had the foresight to acquire more than 10,000 negatives of other photojournalists, speculating that they would be easier to develop and reproduce in the future.

After the introduction of halftone in the printing of New York’s The Daily Graphic in 1880, photographs gradually became a staple of news reporting. The development of flash photography and the increased portability of cameras increased coverage, but costs still meant that engravings played an equal role until the 1920s. The arrival of the wirephoto in 1921 allowed syndicated photographers to send through their images with speed. The following introduction of the first commercially successful 35mm camera, the Leica A, in 1925, meant the availability of photographs began to increase exponentially. The golden age that followed spanned three decades, from the 1930s through to the end of the 1950s. With the advancements in technology and a growing interest in visual storytelling, this period brought extraordinary developments in sports, social and crime photography, while photojournalists covering the major conflicts of this era got closer to the action than ever before.

The golden age witnessed the emergence of many influencial magazines and newspapers such as Life magazine, which played a pivotal role in propelling photojournalism into the mainstream. Launched in 1936, Life became renowned for its extensive use of photographs to tell stories. The magazine’s large format and high-quality printing allowed for impactful and immersive visual narratives. Life covered a wide range of subjects, from war and politics to human interest stories and cultural phenomena. Through the lens of its photographers, such as Margaret Bourke-White, W. Eugene Smith, and Alfred Eisenstaedt, Life brought the world’s events and people into the homes of millions of readers.

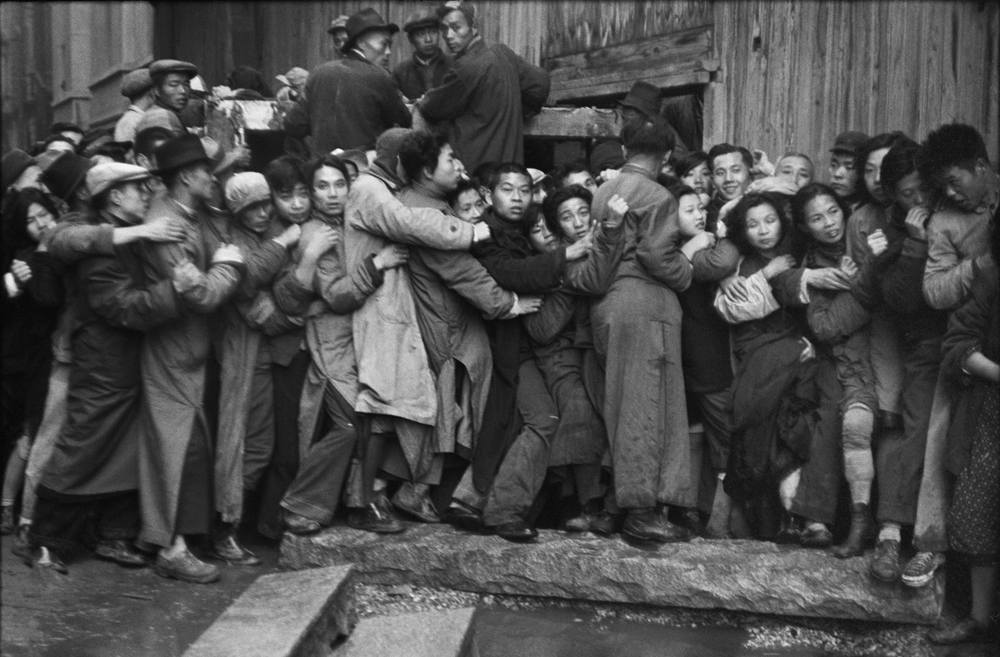

Magnum Photos (a cooperative agency founded in 1947 by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson and David “Chim” Seymour) was another significant milestone of the Golden Age, represented a departure from traditional media outlets. It provided a platform for photographers to document and distribute their work independently, allowing them to retain their own copyright and creative control over their images. This cooperative agency empowered photographers to pursue stories that mattered to them, covering a wide range of topics from conflicts and social issues to cultural events. Magnum photographers would pitch group projects to publications and focus on long-term personal projects funded in part by the resale of their images through the Magnum archive.

Early work produced by Magnum photographers sits firmly within the wider move towards humanism in Europe after the horrors of World War II. However, Magnum’s roots stretch back into the inter-war period. Capa, Cartier-Bresson and Seymour were working in France when the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) broke out. Capa and Seymour had already fled the rising tide of anti-Semitism in Eastern Erope, and all supported the French Popular Front’s fight against fascism. The war in Spain saw the combining of two of the key elements in early twentieth century photojournalism: the use of the hand-held camera and the birth of picture magazines. It was also the catalyst for Capa’s rise to fame with photographs such as Death of a Loyalist Militiaman (1936).

After World War II, Cartier-Bresson travelled in India and Asia (the area of the world allotted to him as a member of Magnum) and in 1952 published his manfesto on photography, Images à la Sauvette (The Decisive Moment), setting out his belief in photography’s ability to elevate reality.

Capa met Magnum’s fourth member, Rodger, in Naples during the Allied advance in 1943 when both worked for Life. An Englishman, Rodger had made his name with his images of the Blitz in the magazine. He went on to photograph the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which proved such a harrowing experience that he gave up war photography. After the war he travelled in Africa and the Middle East, where he curated stories about local people and wildlife.

Magnum Photos grew quickly as other press photographers easily identified with their mission. Swiss photographer Werner Bischof (1916-54) was the first to officially join in 1949. Like Magnum’s founders, Bischof felt that photography had the ability to change public opinion, and he was wary of what he saw as the sensationlism and superficiality of the magazine business. Magnum Photos quickly became known for its commitment to photographic excellence and its unique approach to storytelling, marked by a strong sense of humanism and empathy.

The tension between journalism and art is visible across the Magnum portfolio. In contrast to Capa’s imperfect, immediate picture-taking, the work of Cartier-Bresson represents a considered, composed approach. However, all Magnum photographers tell a story using a traditional photojouanlistic narrative built from groups of images that follow the arc of a story. Over the years, Magnum’s members not only recorded the major historical events of the day but also photographed key figures from popular culture, like Capa’s photoshoot of Pablo Picasso. Magnum Photos has continued to shape the landscape of documentary photography, influencing generations of photographers and contributing to our collective understanding of the world.

The Golden Age of photojournalism also witnessed the rise of influential photo essays. These essays, often published in magazines, used a series of photographs to tell a cohesive and compelling story. One notable example is W. Eugene Smith’s essay “Country Doctor,” published in Life magazine in 1948. Smith spent 23 days documenting the life of Dr. Ernest Ceriani, a dedicated general practitioner in rural Colorado. The photo essay provided an intimate and in-depth portrayal of the challenges and triumphs experienced by Dr. Ceriani, capturing the essence of his work and the community he served.

Another iconic photo essay is Gordon Parks’ “The Harlem Gang Leader,” published in Life magazine in 1948. Parks spent several weeks with the gang leader, Red Jackson, and his group in Harlem, documenting their lives and struggles. The photo essay challenged stereotypes and shed light on the complex social dynamics of urban communities.

The impact of the Golden Age of photojournalism was profound. The power of visual storytelling through photography allowed photojournalists to capture significant events and human stories, shaping public opinion and provoking social change. The photographs of this era became iconic symbols of their time, evoking emotions and sparking conversations.

The Golden Age of photojournalism was a transformative period in the history of the medium, paving the way for future generations of photographers and further influencing the development of the field. It established the importance of visual narratives and the role of photojournalists as witnesses to history. Influential publications such as Life magazine and Magnum Photos provided platforms for talented photojournalists to capture and communicate significant stories. Through their images, photographers like Margaret Bourke-White, W. Eugene Smith, and Gordon Parks brought the world into the homes of millions, shaping public consciousness and inspiring social change. The legacy of this era continues to resonate today and can be seen in contemporary publications, documentary photography projects, and the continued pursuit of truth through images.